In the vast microvascular network of the cardiovascular system, capillaries operate as the principal exchange interface between circulating blood and tissue cells. These microscopic vessels, composed primarily of a single layer of endothelial cells, enable oxygen and nutrient delivery, waste removal, fluid balance, and precise local regulation of perfusion. Capillaries also participate in thermoregulation, immune surveillance, hemostasis, and tissue repair.

Far from passive conduits, capillaries form a dynamic, responsive platform that maintains homeostasis in every organ system. This educational overview examines capillary structure and types, exchange mechanisms, Starling forces and the endothelial glycocalyx, local flow control, organ-specific features, pathophysiology when microcirculation fails, and practical clinical assessment relevant to nursing practice.

What Function Do Capillaries Serve in the Cardiovascular System | Exchange, Fluid Balance, Microcirculation

Capillaries at a Glance-Structure, Scale, and Distribution

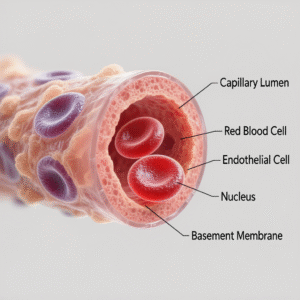

- Definition: Capillaries are the smallest blood vessels linking arterioles to venules and forming capillary beds in virtually all tissues.

- Scale: Lumen diameter typically 5–10 μm, accommodating red blood cells (RBCs) in single file; total length across the body extends thousands of kilometers; aggregate surface area is immense, supporting robust exchange.

- Wall architecture:

- Endothelium: single-cell layer with tight or looser junctions depending on organ function.

- Basement membrane: thin extracellular matrix supporting endothelial cells.

- Pericytes: mural cells regulating stability, permeability, and angio-remodeling.

- Endothelial glycocalyx: carbohydrate-rich luminal layer crucial to barrier function, shear sensing, and revised Starling fluid dynamics.

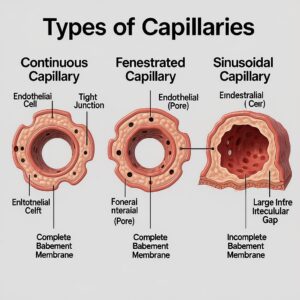

Types of Capillaries-Permeability Tailored to Organ Needs

Continuous Capillaries

- Features: Uninterrupted endothelium with tight junctions; small intercellular clefts; selective permeability.

- Locations: Skeletal and cardiac muscle, skin, lung, and especially the brain (blood–brain barrier).

- Functional note: In the brain, tight junctions, pericytes, and astrocyte end-feet create stringent control over solute passage.

Fenestrated Capillaries

- Features: Endothelial cells contain pores (fenestrations) that facilitate higher fluid and solute flux.

- Locations: Endocrine organs, intestinal mucosa, choroid plexus, and renal glomeruli (specialized filtration barrier with podocyte slit diaphragms).

- Functional note: Supports rapid exchange of hormones, nutrients, and filtrate.

Sinusoidal (Discontinuous) Capillaries

- Features: Large gaps between endothelial cells; discontinuous basement membrane; slow blood flow; high permeability to cells and macromolecules.

- Locations: Liver (sinusoids), spleen, bone marrow, and some endocrine organs.

- Functional note: Enables trafficking of immune cells, plasma proteins, and large particles; critical for hematopoiesis and protein processing.

Primary Functions-What Capillaries Do Every Second

1) Gas Exchange: Oxygen Delivery and Carbon Dioxide Removal

- Oxygen transport: Hemoglobin-bound oxygen diffuses from blood to tissues along a partial pressure gradient; the gradient is maintained by mitochondrial oxygen consumption.

- Carbon dioxide removal: CO2 diffuses from tissues into blood; transported as bicarbonate, carbaminohemoglobin, and dissolved gas; exhaled in lungs via pulmonary capillaries.

- Determinants:

- Fick’s law: exchange proportional to surface area, diffusion coefficient, and partial pressure gradient; inversely proportional to membrane thickness.

- Transit time: RBC passage allows diffusion to near-equilibrium in healthy states.

- Local factors: temperature, pH, and CO2 modulate hemoglobin affinity (Bohr and Haldane effects), optimizing unloading/loading in systemic vs pulmonary beds.

2) Nutrient Delivery and Waste Clearance

- Nutrients: Glucose, amino acids, fatty acids, vitamins, electrolytes, water.

- Wastes: Lactate, urea, creatinine, metabolites from cellular respiration and biosynthesis.

- Transport pathways:

- Diffusion: primary route for small solutes and gases.

- Paracellular transport: through intercellular clefts (regulated by junction proteins).

- Transcytosis: vesicular transport (e.g., albumin) via caveolae and receptor-mediated pathways.

- Fenestrations and sinusoidal gaps: specialized high-flux routes in endocrine, renal, hepatic, and marrow tissues.

3) Fluid Balance: Starling Forces and the Endothelial Glycocalyx

- Classic Starling view: Net filtration at arterial ends (capillary hydrostatic pressure > plasma oncotic pressure) and reabsorption at venous ends (oncotic > hydrostatic).

- Revised Starling principle: The endothelial glycocalyx creates a subglycocalyx oncotic environment; most tissues favor filtration with minimal reabsorption; lymphatic drainage returns interstitial fluid to circulation.

- Forces governing fluid movement:

- Capillary hydrostatic pressure (Pc) pushes fluid outward.

- Interstitial hydrostatic pressure (Pi) pushes inward (often near 0 or slightly negative).

- Plasma oncotic pressure (πc) pulls fluid inward due to plasma proteins (especially albumin).

- Interstitial oncotic pressure (πi) pulls outward; subglycocalyx oncotic pressure is pivotal in revised models.

- Clinical correlate: Edema develops when filtration overwhelms lymphatics or when oncotic or endothelial integrity is disrupted.

4) Regulation of Microvascular Flow and Systemic Pressure

- Resistance and pressure: Arterioles and precapillary sphincters control entry into capillary beds; changes in tone modulate systemic vascular resistance and blood pressure.

- Local control mechanisms:

- Myogenic response: smooth muscle constricts when stretched and relaxes when pressure drops.

- Metabolic regulation: increased CO2, H+, adenosine, K+, and hypoxia promote vasodilation, matching flow to metabolic demand.

- Endothelial mediators: nitric oxide (NO) and prostacyclin dilate; endothelin and thromboxane constrict.

- Shear stress: flow-induced endothelial signaling enhances NO release.

- Micro-rheology:

- Fåhræus–Lindqvist effect: apparent viscosity declines in small vessels, facilitating flow.

- RBC deformability and axial migration reduce resistance; plasma skimming alters local hematocrit.

5) Thermoregulation: Skin Microcirculation

- Heat dissipation: Cutaneous capillaries and arteriovenous anastomoses adjust perfusion under sympathetic control.

- Environmental adaptation: Vasodilation enhances heat loss in warm conditions; vasoconstriction preserves core temperature in cold environments.

6) Immune Surveillance and Inflammation

- Leukocyte trafficking:

- Rolling: selectin-mediated tethering on activated endothelium.

- Firm adhesion: integrin–ICAM/VCAM interactions.

- Diapedesis: transmigration through junctions to reach inflamed tissue.

- Permeability changes: Histamine, bradykinin, and inflammatory cytokines loosen junctions; increased permeability facilitates immune cell and protein access but can promote edema.

- Sepsis and endotheliitis: Dysregulated inflammation injures endothelium and glycocalyx, causing capillary leak and microthrombi.

7) Hemostasis, Antithrombotic Balance, and Repair

- Endothelium maintains a delicate balance:

- Antithrombotic: NO, prostacyclin, thrombomodulin, heparan sulfate protect against clot formation.

- Prothrombotic upon injury: von Willebrand factor and tissue factor support platelet adhesion and coagulation.

- Angiogenesis: VEGF, FGF, and angiopoietins drive new vessel sprouting for wound healing and remodeling; pericytes stabilize nascent capillaries.

8) Endocrine Distribution and Paracrine Signaling

- Fenestrated beds in endocrine organs enable rapid hormone entry into circulation.

- Paracrine factors from endothelium and perivascular cells modulate local tone, permeability, and immune cell behavior.

Organ-Specific Capillary Specialization

Pulmonary Capillaries-External Respiration

- Structure: Extremely thin air–blood barrier formed by alveolar epithelium, fused basement membranes, and capillary endothelium.

- Function: Oxygen uptake, CO2 elimination; matched to ventilation via hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction that directs flow to better-ventilated alveoli.

- Clinical link: Chronic bronchitis and COPD create ventilation–perfusion mismatch, disturbing alveolar–capillary exchange; care plans addressing bronchitis (see content clusters such as a bronchitis nursing diagnosis care plan) routinely consider gas exchange impairment.

Cerebral Microcirculation- The Blood–Brain Barrier (BBB)

- Features: Tight junctions, minimal transcytosis, abundant pericytes, astrocyte end-feet.

- Function: Precisely regulates ionic and molecular traffic to protect neural function.

- Pathology: Ischemia, hypertension, or inflammation can disrupt the BBB, leading to edema and neuronal injury.

Renal Glomerular Capillaries-Filtration Specialists

- Features: Fenestrated endothelium, basement membrane, and podocyte slit diaphragms.

- Function: Ultrafiltration driven by high glomerular hydrostatic pressure; produces primary urine.

- Pathology: Diabetic nephropathy and glomerulonephritis alter permeability and filtration dynamics.

Hepatic Sinusoids-Macromolecular Exchange

- Features: Discontinuous endothelium and basement membrane with Kupffer cells for immune surveillance.

- Function: Protein synthesis, detoxification, and nutrient processing; high permeability supports hepatocyte function.

- Pathology: Cirrhosis distorts sinusoidal architecture, increasing resistance and causing portal hypertension.

Skeletal and Cardiac Muscle-High-Demand Delivery

- Features: Dense capillary networks; recruitment increases during exercise to augment oxygen and nutrient delivery.

- Regulation: Metabolic vasodilation and shear stress rapidly adjust flow to workload; chronic training elevates capillary density.

Homeostatic Roles-Integration Across Systems

- Oxygen delivery (DO2) vs consumption (VO2): Capillaries enable flexible oxygen extraction according to tissue demand; extraction ratio rises in shock.

- Acid–base balance: CO2 removal and bicarbonate trafficking support pH regulation.

- Lymphatic partnership: Excess interstitial fluid and macromolecules return via lymphatics, preserving volume and preventing edema.

- Neurohumoral integration: Hormones and autonomic signals converge on the microcirculation to coordinate systemic responses.

When Capillaries Fail-Microcirculatory Pathophysiology

Edema-Fluid Balance Disruption

- Mechanisms:

- Elevated Pc: heart failure, venous obstruction.

- Reduced πc: hypoalbuminemia from liver disease, nephrotic syndrome.

- Increased permeability: inflammation, sepsis, burns, allergic reactions.

- Lymphatic impairment: lymphedema after surgery or radiation.

- Clinical features: Pitting or non-pitting swelling; functional limitations; skin changes; risk for infection and ulceration.

Diabetes Mellitus-Microangiopathy

- Lesions: Basement membrane thickening, pericyte loss, endothelial dysfunction.

- Consequences: Retinopathy (microaneurysms, neovascularization), nephropathy (albuminuria), neuropathy (ischemia), impaired wound healing.

Hypertension-Microvascular Rarefaction

- Changes: Reduction in capillary density; increased tone; endothelial dysfunction.

- Impact: Higher peripheral resistance, diminished tissue perfusion, target-organ damage.

Sepsis and Septic Shock Endothelial Injury

- Features: Glycocalyx shedding, barrier disruption, heterogeneous perfusion, microthrombi.

- Biomarkers: Syndecan‑1 and hyaluronan indicate glycocalyx damage.

- Clinical impact: Capillary leak, refractory hypotension, organ dysfunction.

Chronic Lung Disease V/Q Mismatch

- COPD and chronic bronchitis: Mucus and airway remodeling impair ventilation, while capillary perfusion persists; mismatch reduces effective oxygenation at the alveolar–capillary interface.

Tumor Angiogenesis-Abnormal Neovasculature

- Traits: Disorganized, leaky, and tortuous microvessels with uneven flow.

- Consequences: Hypoxia, acidosis, and variable drug delivery; EPR (enhanced permeability and retention) effect influences pharmacokinetics.

COVID-19 and Microthrombi

- Observations: Endotheliitis, platelet activation, and microvascular thrombosis implicated in hypoxemia and multi-organ effects.

Clinical Assessment-Nursing Considerations at the Bedside

Capillary Refill Time (CRT)

- Method: Press on the nail bed or skin until blanching; release and count time until color returns.

- Reference: Often ≤2 seconds in warm environments for adults; longer times may reflect hypoperfusion, cold exposure, or vasoconstriction.

- Caveats: Age, ambient temperature, skin pigmentation, and lighting affect interpretation; integrate with broader perfusion assessment.

Skin Temperature, Color, and Mottling

- Indicators: Cool, pale, or mottled extremities suggest vasoconstriction or low flow; warm, flushed skin may reflect distributive states.

Edema Evaluation

- Pitting scale (1+ to 4+), anatomic distribution, symmetry, and relation to body position.

- Monitoring: Circumferential measurements, daily weights, lung auscultation for crackles, jugular venous distension, and output trends.

Pulse Oximetry and Tissue Oxygenation

- Limitations: Poor perfusion, vasoconstriction, motion artifacts, and dyshemoglobinemias alter accuracy.

- Adjuncts: Near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) for regional tissue oxygenation; lactate trends for global hypoperfusion.

Peripheral IV Integrity and Extravasation Prevention

- Considerations: Catheter size-to-vein ratio, securement, frequent site checks, prompt response to infiltration or phlebitis.

- Vesicants: Avoidance of peripheral administration when possible; if necessary, strict monitoring and established protocols.

Wound Care and Microvascular Support

- Strategies: Pressure offloading, moisture balance, atraumatic dressings, management of edema, glycemic control, and smoking cessation support.

- Advanced options: Negative pressure wound therapy, vascular referral for arterial insufficiency, adjunctive oxygen therapies when indicated.

Measurement and Research Tools in Microcirculation

- Nailfold capillaroscopy: Visualizes capillary loops and morphology (useful in rheumatologic conditions).

- Sidestream dark field and orthogonal polarization spectral imaging: Bedside observation of sublingual or mucosal microcirculation in critical care.

- Laser Doppler flowmetry and laser speckle contrast imaging: Assess perfusion dynamics.

- Transcutaneous oxygen tension (TcPO2): Evaluates skin oxygenation in vascular disease.

Practical Strategies for Preserving Capillary Health

- Cardiometabolic fitness: Regular aerobic and resistance exercise enhances capillary density and endothelial function.

- Nutrition: Adequate protein, micronutrients, and omega‑3 fatty acids support endothelial health; sodium moderation assists fluid balance.

- BP and glucose control: Tight management reduces endothelial damage and microangiopathy progression.

- Tobacco avoidance: Nicotine and carbon monoxide impair microvascular tone and oxygen delivery.

- Environmental moderation: Thermal extremes and sustained pressure compromise skin perfusion; repositioning and protective supports reduce risk.

- Hydration and mobility: Adequate fluid intake and routine movement sustain venous return and lymphatic flow.

Summary Core Functions of Capillaries in One View

- Exchange: Oxygen, CO2, nutrients, and wastes move efficiently across an ultrathin barrier.

- Fluid homeostasis: Starling forces and the glycocalyx govern filtration; lymphatics return fluid to circulation.

- Flow regulation: Local metabolic, myogenic, and endothelial mechanisms tailor perfusion to demand.

- Systemic influence: Microcirculatory resistance contributes to blood pressure control.

- Defense and repair: Leukocyte trafficking, controlled permeability, hemostasis, and angiogenesis support immune response and healing.

- Specialized roles: Organ-specific capillary designs meet unique physiologic priorities.

- Clinical relevance: Perfusion, edema, and microvascular integrity inform assessment, interventions, and outcomes.

Conclusion

Capillaries are the operational core of the cardiovascular system, translating macro-hemodynamics into cellular-level delivery and clearance. Through precise balance of permeability, pressure, and local regulation, these vessels maintain oxygenation, nutrient supply, waste removal, fluid homeostasis, and coordinated immune and repair responses. In health, capillaries achieve remarkable efficiency and adaptability. In disease, microvascular dysfunction drives edema, hypoperfusion, organ injury, and impaired healing. For health professionals, mastery of capillary physiology sharpens assessment and guides interventions-whether evaluating capillary refill time, grading edema, optimizing oxygen delivery, or coordinating care for microangiopathic complications. The microcirculation’s quiet labor is essential to every clinical goal: stable perfusion, balanced fluids, and recovery that endures.

FAQs About Capillaries

Q1: How do capillaries differ from arteries and veins?

Arteries propel blood away from the heart under higher pressure through muscular walls; veins return blood at lower pressure aided by valves. Capillaries, composed of a single endothelial layer, form exchange sites where gases, nutrients, and fluid move between blood and tissues.

Q2: Which capillary types exist and where are they found?

Three main types exist: continuous (muscle, skin, lung, brain/BBB), fenestrated (endocrine organs, intestines, renal glomeruli), and sinusoidal/discontinuous (liver, spleen, bone marrow). Increasing permeability from continuous to sinusoidal aligns with each organ’s exchange requirements.

Q3: What determines whether fluid filters out of or returns into capillaries?

Net movement depends on hydrostatic and oncotic pressures across the endothelial barrier and the state of the glycocalyx. Most tissues favor filtration with lymphatic return, rather than large-scale reabsorption, under the revised Starling principle.

Q4: Can capillaries regenerate after injury?

Angiogenesis and vascular remodeling occur in development, wound healing, and certain pathologies. Endothelial cells proliferate and migrate under signals such as VEGF and FGF, while pericytes stabilize maturing microvessels.

Q5: How does diabetes impact capillary function?

Chronic hyperglycemia promotes basement membrane thickening, oxidative stress, and pericyte loss, leading to microangiopathy. Consequences include retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, and delayed wound healing due to impaired perfusion and barrier alterations.